|

| Source - Visual Capitalist |

The source of this graphic - Kalo Gold - appears to be a gold speculation company focusing on Fiji and British Columbia. I haven't the foggiest idea whether they're a reputable company or some sort of scammers' paradise.

|

| Source - Visual Capitalist |

Glass is pretty awesome.

Here Dr Derek explores the history of glassmaking through modern glass like Gorilla Glass including how modern glass is made stronger, how it's tested, why glass is transparent for light, and lots more.

Let's be honest. That was predictably dumb.

tl;dr - Yes, he can, but it's expensive and involves a whole lot of oxidation.

Damascus steel has a noteworthy pattern that is really what Alec is trying to reproduce with the titanium shown in these videos. Here he starts with alternating grades of titanium stacked then forge welds them together.

The steps required to then anneal and machine the titanium billet that he produces are labor-intensive to say the least.

But he does get some cool rings out of the process.

Parts 2 and 3 of the series are after the jump.

The widening gyre...

Yes, there's a garbage patch in the center-ish of the Pacific Ocean.

That garbage patch is not anything worth looking at, though. It's an area of higher than average concentration of plastic waste, but it's not something you could walk across or would have trouble boating through. Even a higher density area isn't necessarily a high density area.

As this video reveals, the most common photos attributed as being of the garbage patch are not of the garbage patch. They're of near-shore, highly polluted areas - which might actually be easier to clean up than the garbage patch would be - if we even should clean it up.

The video goes on to explore the sources of plastic pollution (hint - mostly not littering), the value of recycling (limited but worth doing), the role of big corporations in producing plastic waster (suck it, Coca Cola), the problems with microplastics (bad, very bad), and the need to reduce more than reuse and recycle.

These kinds of videos are way too easy to find on YouTube.

Plastics bad...we need to use less of them.

...and I write that as I sit beside of plastic bottle of Coke Zero Cherry that I'm drinking today.

"All you need to do is melt some sugar."

Yeah, there's a lot more than that involved in making sugar glass.

You need to make sure the 'glass' remains amorphous so it stays translucent - which is is a little tougher than it seems.

And the sugar shouldn't actually be sucrose but rather isomalt.

...and the stuff you make isn't exactly safe to break across a friend's head.

Not a lot of science presented in that first video, so let's try another one.

Sugar glass itself isn't the solution to single use plastics.

It's too brittle and too water soluble.

But it sounds like the composite of sugar glass (isomalt) and sawdust - particularly with a waterproof coating - might be a promising possibility.

I absolutely adore the St Louis arch - technically The Gateway Arch - and have been to the top at least a half dozen times. If I had my druthers, I would get to the top every time I'm in St Louis, but my wife and mother-in-law are less interested, so I merely admire it crossing the bridge each time we're in town.

One of our campers in Boise this summer explained that she had a lesson in her science class about the final topping-out ceremony of the arch, it being interesting because one side was in more direct sun. This lead to that sun side expanding more than the other, causing the two legs not to initially line up and the gap for the keystone to be too narrow if not for the hydraulic jacks installed to spread the legs apart.

Check out the details in the above video at 0:50 and in from the Arch's wikipedia article...

It was slated to be inserted at 10:00 a.m. local time but was done 30 minutes early because thermal expansion had constricted the 8.5-foot (2.6 m) gap at the top by 5 inches (13 cm). To mitigate this, workers used fire hoses to spray water on the surface of the south leg to cool it down and make it contract. The keystone was inserted in 13 minutes with only 6 inches (15 cm) remaining. For the next section, a hydraulic jack had to pry apart the legs six feet (1.8 m). The last section was left only 2.5 feet (0.76 m). By noon, the keystone was secured.

Brilliant, man. hose down the hot side with cold water.

How cool is that?

I'm sorry...I know...it's a corny joke...but it was right there...I couldn't help myself...

A month or so ago, my wife brought home an Indestructibles book. She'd picked it up from our local Target store as a baby shower gift for a coworker and said it was made of a neat material that didn't rip.

I asked if it was Tyvek, knowing that Tyvek is a rip-stop fabric. She, a successful Appalachian Trail thru-hiker knows Tyvek as a lightweight ground cloth, and she said she wasn't sure whether the books were Tyvek or not.

So off I went on an internet hunt...

What are Indestructibles made of that is so durable yet paperlike and delightful for my baby?

Indestructibles are printed on a synthetic material made from flashspun high-density polyethylene fibers (getting technical here, we know). It feels like paper, but liquid water cannot pass through it and it is very difficult to tear.

Flashspun fabric is a nonwoven fabric formed from fine fibrillation of a film by the rapid evaporation of solvent and subsequent bonding during extrusion.

Tyvek (/ˈtaɪ.vɛk/) is a brand of synthetic flashspun high-density polyethylene fibers. The name Tyvek is a registered trademark of the American multinational chemical company DuPont, which discovered and commercialized Tyvek in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Tyvek's properties—such as being difficult to tear but easily cut, and waterproof against liquids while allowing water vapor to penetrate—have led to it being used in a variety of applications.

waterproof...liquid water cannot pass through it...difficult to tear but easily cut...very difficult to tear...flashspun high-density polyethylene fibers...flashspun high-density polyethylene fibers

This video is from 2009, so some of the details are admittedly a little dated, but the overall concepts - that we need to reduce our usage of materials in spite of the business community's desire for us to increase our usage and many governments' business-friendly leanings - are as relevant today as they were fifteen years ago (as I type this, anyway).

The channel has continued to make videos, posting their most recent (as of me typing this on July 4th, 2024) one in June of 2024, and they have a website with information on how to get involved in their campaign to decrease materials usage - particularly plastics and materials that end up in landfills.

|

| From online pdf |

The article - from Physics Today's January, 2016 issue - goes into peer-reviewed detail of the thermodynamics of glass's formation, methods of forming glasses, a defining glass as a specific state of matter. I know the science would blow the heads off of our Princeton matsci students and would likely push my AP chemistry students to their very edges of understanding, but I learned a lot in reading the article and will go back through it a few more times to get a little more out of it.

The full article is available as a pdf as published or without the fancy title page.

Depleted uranium just sounds terrifying. Sure, you can pick up some uranium ore and yellowcake from United Nuclear, but trying to buy depleted uranium is going to likely be a little dodgier.

With that being said, the US military has used depleted uranium (DU) as a source of armor penetrating ammunition over the years. I thought - wrongly from the video above - that the DU was simply used because of its high density and nature otherwise as nuclear waste. Today's video posits that there are quite a few other advantages of DU in high-caliber munitions applications.

There are also some seemingly obvious health risks involved in living in an area where spent DU shells are peppering the ground or having been in a tank where DU rounds entered and as least slightly vaporized. The video also goes through those health risks and says that they have largely been disproven, though I would be skeptical and appreciate that many military branches are "not considering depleted uranium anymore because of the environmental problems associated with it, be [they] real or perceived."

I think I'll stick to good ol' tungsten for my armor piercing needs.

That looks a whole lot like solgels to me, but I'll admit that my knowledge of solgel chemistry is about twenty five years out of date and based on a single summer of research at Miami University (no, not University of Miami).

The video summarizes researchers' findings that amino acids can form glasses with an index of refraction close to that of silica glass, adhesive properties, and a natural inclination to form convex lens shapes...and that self heal themselves as they rehydrate themselves.

There simply are no words.

I mean throughout this twenty minute video there literally are no words spoken.

Instead, we just watch a knifemaker craft a single, beautiful knife from initially forge welding stacks of steel together to testing the finished knife.

It's mesmerizing.

Mark Miodownik is the author of one of the better materials science books written for a popular audience, Stuff Matters.

In that book he takes a chapter to explore each of the various material categories and some of that category's most common exemplars.

Here, however, Miodownik looks at glass to see why light can pass through it. Turns out it's all about electron transitions.

As always, be careful out there, folks. This experiment does involve running electricity through a solution.

This process does seem to result in some really pretty crystals.

And I'll admit that I kind of enjoy the simple, non-mugging style that the Backyard Scientist has gotten away from over time.

There is so much happening in manufacturing that I am blown away by.

I understand the absolute minimum basics of forging, stamping, casting, and a few other processes, but this concept of slightly deforming a metal sheet by pushing with two (by the company's founders) end effectors without any mold and just using CNC robotic arms is amazing to watch. The process is referred to as incremental forming.

The amount of computing power required to do all of this is stunning to me.

I think manufacturing might be becoming more complicated over time...just maybe.

This second video is ninety-four minutes of behind the scenes footage that Destin edited down into the thirty minute video up top.

This is a very information dense video explaining...

I toured an asphalt research lab when I helped lead the second year ASM camp at Rowan University a few years back. Before that I'll admit that I hadn't put much thought into the different compositions that make up asphalt roads or the research that went into 'perfecting' the recipes used in road building.

Today's video introduces us to Green Asphalt, a company that is taking asphalt removed from roads and processing that asphalt into a reusable product, preventing hundreds of thousands of tons of asphalt from landfills every year.

I think I wrote it a few weeks back, but man, we make a lot of waste.

Obsidian...opals...tektites...fulgurites (including their subsets, apparently)...glass sponges

I knew about a couple of those, but I'll admit that I'd never heard of glass sponges or tektites, and I didn't really think of opals being glass.

We produce a great deal of waste. That's not a very debatable statement.

This video visits a London restaurant that is attempting to have zero waste from his restaurant.

From making the pendant shades out of waste seaweed to forming their own pottery on site and glazing that pottery with ground up waste wine bottles, the restaurant attempts to have nothing thrown away from day to day.

They ferment much of their food scraps that would normally be wasted and thrown away.

They upcycle their plastic bags into serving plates.

Somehow the ice cream is made from waste bread.

All in all, it's a place that I would love to study more but that I'm not sure I would actually enjoy. Some of the cuisine seems to be awfully fancy, and I'm not sure that my tastes are in line with.

Check out Silo if you're ever in London - and if you can actually get a reservation.

A Failure of the Imagination from ENGLAND your ENGLAND on Vimeo.

So, a bit of a story...

I was watching this video on trying to build 3d printed objects by using half layer offsets...

|

| 5:38 in the above video |

It's tough to repair a building that is a single piece of material.

That's the short answer to the rhetorical question posed in the video's title, though the host goes into a lot more detail than that simple sentence.

He also explains that making a house out of a single material defeats the purpose of using different materials on the inside (drywall, for example) and outside (bricks or siding, for example) of the house; that no single material will work for walls, doors, and windows necessitating the merging of the 3d printed materials with some sort of additional structure for those features, partially defeating the advantages of 3d printing; and the 3d printed house's size is restricted by the size of gantry on which the 3d printer moves.

I subscribe to Stewart Hicks's channel, primarily covering architecture and focusing on the Chicagoland area with a frequent highlighting of Frank Lloyd Wright's work. Most of the videos aren't on material science but rather on the architecture.

A few years back I took a workshop from the American Ceramic Society and got a free Materials Science Classroom Kit.

The workshop was a bit of a bust because of a minor snowstorm that kind of cancelled the workshop even though half the participants still showed up, and the presenters did a game job of presenting the workshop as best they could with their limited staff and attendees.

In case you'd thought about getting this kit or taking the workshop, I thought I'd run through what you get for $249 (seriously, that's the price as of my posting of this info.)

The box contains...

"The lessons are some of the most well-written lessons I’ve seen in the industry. They are truly great and valuable for all science teachers!"

That's going to be a very contemporarily pretty airport.

I don't get the idea of an airport where people will just come to hang out as a community space because I'm thinking that's going to freak out a whole bunch of security folks, but in the long run that's not a materials question, so I'll leave that aside for now.

The mass timber movement seems to go back to basics, using bonded wood from supposedly sustainable forests to build gorgeous buildings. Here's to hoping that it works.

Anything more than totally naked sporting competition is essentially a materials question.

Wooden tennis racquets gave way (briefly) to aluminum and then to composite racquets.

Wooden baseball bats became aluminum then composites.

Similar progressions took place for pole vaulting and nearly every other sport.

In running, however, the materials question mostly shows up in the running shoes, and Nike's Vaporfly is the current materials leader in that realm.

More videos after the jump...

I am both hopeful about and horrified at the prospect of enzymes that will break down plastics.

I'm hopeful because the man-made polymers that we have been creating and covering our world with for decades now are going to have to be broken down somehow, sometime. If decomposers are beginning to be able to process them into harmless - or even beneficial - products, that's great.

...but we have a lot of currently in-use polymers that we don't necessarily want to start breaking down into gray goo just yet.

...and if we find a way to make polymers break down more easily, will that just encourage us to make more of those polymers rather than stopping the production of them sooner?

I do love a pretty mosaic.

Park Gruell in Barcelona is one of the most magnificent mosaic collections that I've ever seen, and I'm a sucker for pretty much any mosaic construction. This video does make me a little sad, however, as I wasn't aware that the glass industry had largely left Venice, one of its historic homes.

Those are absolutely gorgeous tiles. When my wife and I were redoing our shower, I went with a raku tile for the small accent shelf that we added, but if I'd known about these cement tiles before hand, I might've been tempted by them.

Remember, of course, that these are cement tiles, not concrete tiles...ceramic not composite...though the layering might make them a laminar composite anyway...hmmm...

I assume these folks are using medieval techniques to build their castle because they want to not because they're just stubbornly French, right?

I remember in Thomas Thwaites's Toaster Project video that he mentioned needing to go further and further backwards in time when he wanted to bring the scope of industrial processes down to human-sized scales. If he wanted to smelt iron for a single toaster, he wasn't going to build an industrial blast furnace; he was going to find how they heated iron ore thousands of years ago.

That concept resonates as I see an ancient castle being built in modern times but with ancient techniques. They aren't looking for large-scale, industrial processes. They're looking for ancient craftsman methods.

If you want to see more, I'm putting a few more videos after the jump.

I was at Indian Lake in northern Ohio recently and saw a vehicle/machine driving back and forth in the water about twenty feet out from Oldfield Beach. When I asked what the machine was doing, I was told that it was chopping up and supposedly harvesting invasive pondweed (details of the plan here) that was plaguing the lake because of its shallowness and prevalence of fertilizer run-off from nearby farms leading to blue-green algae blooms and near dead zones.

I don't have any idea what they're doing with the pondweed that they harvest from Indian Lake, but I feel like I might was to put those folks in touch with the subject of today's video as he seems to have found something to do with unwanted aquatic plant growth.

As I mentioned last week, I toured the Indianapolis Art Museum's conservation lab as part of our summer ASM materials camp a decade or so ago. It was a great tour given by Dr Gregory Smith, star of this series of videos through which he explains the process of verifying the age and pedigree of an Uzbek Coat of Many Colors.

The rest of the four-part series is after the jump.

Give 'em a break, alright?

It was the pandemic. People were trapped in their houses. They were doing their best to create content that was interesting and that could be enjoyed remotely.

No, a video of two people talking remotely to each other while narrating a slide show isn't necessarily the most exciting of presentations, but I can vouch for Dr Smith being an entertaining guy. He gave me and our summer ASM campers a tour of the Indianapolis Museum of Art's conservation lab about ten years ago, and it is one of the more unexpectedly great tours that I've been on through those summer workshops.

Take some time and see what Dr Smith has to teach us about art conservation and forgery detection today.

Stephanie Kwolek absolutely belongs in the inventors hall of fame, in the women's hall of fame, on the American Chemical Society's website, and on lots of other lists of honorees.

Stephanie Kwolek, you see, invented Kevlar at DuPont in 1965.

The process of making shellac is scientifically fascinating, ridiculously complicated, economically important, and ethically questionable.

Like so many products that are 'natural', shellac amazes me because I have absolutely no idea how anyone would have thought to go through this process to turn bug secretions into a furniture sealant, a citrus fruit polish, a candy coating, and so much more.

"Well, contrary to what you might think, it's not a chemical reaction." ~ 2:17

I'll readily admit that I assumed it was based on a chemical reaction rather than what this video suggests - just after the above quote - the gallium seeps into the grain boundaries between the aluminum crystals and prevents them from holding together as they normally would.

Embrittlement, eh?

I'd eat that for a dollar!

The idea that we can create structural color - akin to that found on the wings of butterflies - using a diffraction grating and some tempered chocolate is pretty amazing.

Diffraction grating isn't too expensive, and chocolate is pretty cheap.

Looks like a fun summer project.

(Or you could just buy yourself some holographic chocolate directly.)

Today's fascinating, possible miraculous composite: ferrock.

From CertifiedEnergy...

Ferrock is created from waste steel dust (which would normally be thrown out) and silica from ground up glass, which when poured and upon reaction with carbon dioxide creates iron carbonate which binds carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into the Ferrock.

Roughly 95% of the Ferrock is made from recycled materials, Ferrock is both stronger and more flexible than normal Portland cement, allowing it to be used in highly active environments where there is a consideration for seismic activity.

From ScienceDirect...

At 28 days, the strength of Ferrock concrete exceeds that of conventional concrete by 13.5 percent for compressive strength, 20 percent for split tensile strength, and 18 percent for flexural strength.

From the University of Arizona...

"This all started from an accidental discovery in a lab, which is actually the way it usually goes," [Ferrock inventory David] Stone says. "That was back in 2002, and I included as much as I knew in my doctoral dissertation. But the work goes on. It has taken years to get just a basic understanding of the chemistry involved. But this shouldn’t be surprising, since scientists are still trying to figure out Portland cement and they’ve had 200 years.

"I am into this for the long haul. Time is on our side, since in this era of global warming unsustainable processes like cement manufacture will have to give way to greener alternatives."

As always, I am guardedly hopeful but skeptical until I start seeing Ferrock showing up in buildings.

I've been to Butte, MT and stood in the shadow of that smelter smokestack.

The legacy of mining in Butte is...complicated.

Clearly the city wouldn't be what it is without its mining past. The richest hill on Earth made this city - at one time, not now - the largest city between Chicago and San Francisco.

But that same mining industry poisoned the land all around that hill, pumping the products of the smelter as high and far as possible from that giant smokestack.

I've posted about the EPA-lead cleanup from the mining industry before, and apparently Anaconda, MT is happy with how the cleanup is going, but it sounds like some of the folks in Butte aren't so happy.

|

| Source - VisualCapitalist |

"What yours is mined." ~ tagline on magnets from the College of Earth and Mine Sciences at the University of Utah

I don't have much to add to today's infographic other than it's amazing to me how much more iron ore we mined than all the other metals combined.

There are certain properties of glass that make this a single-use GLASS FLIPBOOK, namely it's brittleness.

At room temperature, glass is inherently not flexible or workable.

Even the willow glass that our intrepid YouTuber uses in today's video is fragile when bent - less so than normal sodium lime glass would be, but still pretty fragile.

I know what you were wondering: where are all the summer material science teacher camps in 2024?

Well, wonder no more. Here is where they all are.

If you don't know what I'm talking about - first, I'm not sure how you found your way to this blog because I think this is just about the only way people find this blog...second, check out the videos about the camp that I've posted before.

If you're wanting to sign up for one of these camps, head on over to the ASM Education Foundation website and sign the heck up!

In our material science class at Princeton - and in most of the matsci classes that originated from the ASM summer camps, I would imagine - we grow copper (II) sulfate crystals from solution.

It's a fairly easy lab to do, and the students have a high success rate.

For most students, that crystal growing experience is an end, but for others it's just a beginning, a taste of a much richer world of crystal growth.

For those students, crystalverse would be a great resource as it provides instructions for the diy crystal farmer whether they want to grow crystals of copper acetate, monoammonium phosphate, sucrose, alum, sodium chloride, potassium ferrioxalate, or even pyramidal crystals of sodium chloride.

In every case, the procedure is largely the same - make a solution, let the solution cool and evaporate to form seed crystals, continue to let the solution evaporate to grow the seed crystals larger. The great things about the crystalverse website is that it has loads of tips and faqs to help you troubleshoot your growing.

Today you get a whole bunch of videos about making salt (all different from previous salt making videos.)

It seems like such a simple thing - talk salt water from the ocean and boil it down - but there's a lot more to the science of making salt including removing the calcium and magnesium impurities, allowing the crystals to grow to the desired size, and sorting those different crystal sizes.

Who knew that the rate of crystal growth would affect the size of the crystals?

More after the jump...

Self-healing materials could be pretty cool if we get them figured out.

I appreciate the brief dalliance into cold welding between metallic pieces in space - something I've posted about before.

And I appreciate Steve Mould, of course, who sadly keeps his humour (British, natch) mostly in check for this video.

I'm approximately a million hours away from being a structural engineer, but I think I could look at the cracks shown in the video at 6:49, 10:47, and 16:20 and say that maybe they shouldn't be going ahead with moving the bridge into place.

I never would have thought of the shifting forces during the movement of the bridge from its initial fabrication location, but the need to constantly restress the concrete with each move is fascinating. I would think that would require the concrete to be stressed and stressed and eventually over-stressed.

I've been watching videos from Brick Immortar of late and will have another one from the same channel next week, but I could pick probably any of these videos and post them here. They all seem to analyze famous engineering failures, quickly recap the incident, then summarize the causes of the failure.

This one is one I'd heard about and that I've seen discussed as a famous case of plans being adjusted without proper checking to see if that seemingly minor change would be problematic. This is, however, the first video on the incident that I've seen discuss that the original design would have been problematic over time as well.

I'll admit that I do wish today's video would do a little better job of telling what porcelain is rather than just telling why it's so labor intensive to make.

So I went looking around the intertubes to find some definitions of what porcelain is.

From wikipedia...

Porcelain is a ceramic material made by heating raw materials, generally including kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between 1,200 and 1,400 °C (2,200 and 2,600 °F). The greater strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arise mainly from vitrification and the formation of the mineral mullite within the body at these high temperatures.

From Britannica...

Porcelain, vitrified pottery with a white, fine-grained body that is usually translucent, as distinguished from earthenware, which is porous, opaque, and coarser. The distinction between porcelain and stoneware, the other class of vitrified pottery material, is less clear. In China, porcelain is defined as pottery that is resonant when struck. In the West, it is a material that is translucent when held to the light.

From Webster's...

a hard, fine-grained, sonorous, nonporous, and usually translucent and white ceramic ware that consists essentially of kaolin, quartz, and a feldspathic rock and is fired at a high temperature

From Far and Away...

Ceramic is a broad term for various materials that are made by firing clay or other mixtures at extremely high temperatures. Generally, it includes products such as pottery, tiles, and cookware. The surfaces of ceramic can be painted or glazed to create different finishes and styles.

Ceramics are usually broken down into three categories: porcelain, stoneware, and earthenware.

Porcelain is denser than stoneware and earthenware, which makes it the strongest type of ceramic. In addition to its strength and durability, porcelain also has an extremely smooth surface that lends itself well to decorative treatments such as hand painting or airbrushing. Porcelain is also the least porous type of ceramic material, which makes it ideal for use in bathrooms or kitchens where watertightness is important. Earthenware is the softest type of ceramic material and can be very delicate in nature. It also has a tendency to absorb moisture easily.

Earthenware pieces tend to be thicker than their porcelain counterparts due to their lack of strength and durability. As a result, they are often produced in simpler shapes with fewer decorative details since any intricate detail may be too delicate to survive regular use or exposure over time.

Stoneware falls somewhere between porcelain and earthenware in terms of strength and durability making it a popular choice for everyday items like plates or mugs since it can withstand some wear-and-tear but isn’t overly fragile like earthenware pieces tend to be. Stoneware has been used throughout history for many types of items including storage jars, jugs, figurines and table services sets due its versatility in design options depending on the levels at which it’s fired during production processes.

...

Porcelain is a fine-grain ceramic material made from kaolin, a white clay mined in various parts of the world. It is used for tableware, tiles, and other applications where strength, hardness and stain resistance are desired.

Porcelain has an extremely low porosity—it is nearly waterproof—and it is considered to be thermal shock resistant. It can withstand temperatures up to 1800 degrees Fahrenheit and it does not react with chemicals in the same way as other ceramics. Porcelain can accept a wide variety of decorative glazes and finishes, which makes it ideal for many applications.

When comparing porcelain to its relative ceramic, there are some key differences to consider:

Porcelain has a finer grain than ceramic and its ingredients go through more processing before they can be used as a material choice.

Due to its high degree of density, porcelain is more durable than ceramics but it also costs more because of the processing involved in producing the material.

So, there you go...

Arrggghhh, Action Lab again.

I want to hunt down some of those dialectric mirrors. Their non-isotropic reflective materials sound pretty cool.

I am amazed that there is no metal in the material. It's just made of transparent polymer layers in alternating materials with different indices of refraction.

Argh, Action Lab again.

I don't care for the host as a video host, but I do like some of the experiments he gives and the experiments he shows...sometimes.

This video shows noise-damping tape which incorporates a viscoelastic layer to the tape, causing a significant amount of damping for the vibrations in the cookie sheet that Action Lab uses as a frugal gong.

One of my coworkers recommended this video to me, and I respect the video host's adherence to the scientific method. He tests metal from the same source, prepared in the same way, and has multiple test samples for each coating.

I'm not so sure, however, what these rust convertors actually do. I found this in the wikipedia article on rust converters...

Commercial rust converters are water-based and contain two primary active ingredients: tannic acid and an organic polymer. Tannic acid chemically converts the reddish iron oxides into bluish-black ferric tannate, a more stable material. The second active ingredient is an organic solvent such as 2-butoxyethanol (ethylene glycol monobutyl ether, trade name butyl cellosolve) that acts as a wetting agent and provides a protective primer layer in conjunction with an organic polymer emulsion.

Some rust converters may contain additional acids to speed up the chemical reaction by lowering the pH of the solution. A common example is phosphoric acid, which additionally converts some iron oxide into an inert layer of ferric phosphate. Most of the rust converters contain special additives. They support the rust transformation and improve the wetting of the surface.

The title of this video is wrong.

There is no freezing happening. There is recrystallization happening from sodium acetate dissolved in solution.

That's not freezing - a pure liquid turning into a solid like ice turning into water. The host seems to understand that distinction, but he's sloppy on using the term freezing and freezing point somewhat misleadingly. He also is sloppy on liquid versus solution and melted versus dissolved.

Most of this video is an explanation and comparison of the two types of hand warmers - the reusable sodium acetate solution and the single-use iron rusting type. The video host explains the science behind what's happening and judges the single-use to be the better choice - something that I'll leave up to you.

I use both in class for different purposes and different chapters.

|

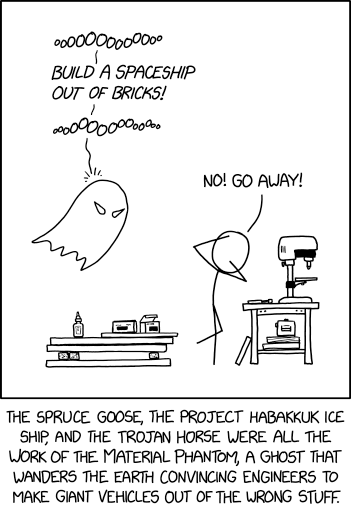

| Source - xkcd Rollover joke - The phantom found Edward Everett Hale a century too early; by the time we invented satellites, the specifics of his 'brick moon' proposal were dismissed as science fiction. |